The UK's only official astronauts to date discuss planning a space mission, trusting crew members and the future of technology in space travel

Helen Sharman and Tim Peake are the only two British astronauts to enter space to date

They made history as Britain’s only two astronauts to date, and Dr Helen Sharman and Major Tim Peake share a belief that teamwork is the most important part of a successful space mission.

Despite their visits to space stations orbiting the planet coming 24 years apart and experiencing the huge advances in technology during that time, the duo insist that having a trust in fellow crew members when hundreds of miles above Earth remains crucial.

Dr Sharman and Major Peake, the only two people to go into space bearing a union flag patch, shared a stage at Microsoft Future Decoded 2019 to discuss their respective missions before, during and after – with their stories containing some key lessons for businesses.

Helen Sharman and Tim Peake on how they became astronauts

Six weeks after Dr Sharman celebrated her sixth birthday, the Apollo 11 mission launched from Florida.

It carried Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, who millions of people across the world would watch take humanity’s first steps on the Moon on 21 July.

Back on Earth, human imagination of what was possible would never be so limited but for Sheffield-born Dr Sharman, the idea of being an astronaut never crept into her mind.

“Going into space wasn’t possible for British people at all so I never considered it,” says the 56-year-old.

“I didn’t spend my entire student life doing astrophysics and I didn’t go to space camps in summer holidays.

“Instead, I did things that were very pragmatic but gave me a lot of opportunities later in life.”

She didn’t even venture far to get her degree, studying chemistry at the University of Sheffield.

A PhD in London was also obtained before working as a research and development technologist at BAE Systems predecessor General Electric Company and then as a chemist for confectionery brand Mars.

It was only when she heard a radio advert urging listeners to apply for Project Juno, a Soviet-British space mission, that she set off towards her eight-day mission to the former Mir space station in 1991 – having beat 13,000 other applicants.

While Chichester-born Major Peake, 47, also applied in response to an advert, he doesn’t share Dr Sharman’s academic background after left school aged 18 with C, D and E grades at A-levels – demonstrating “there’s hope for everyone”.

He joined the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and became a helicopter pilot, later studying for a degree in flight dynamics and evaluation before leaving the armed forces in 2009 after 17 years’ service.

Major Peake finished ahead of more than 9,000 other applicants to win one of six places on a new European Space Agency astronaut training programme.

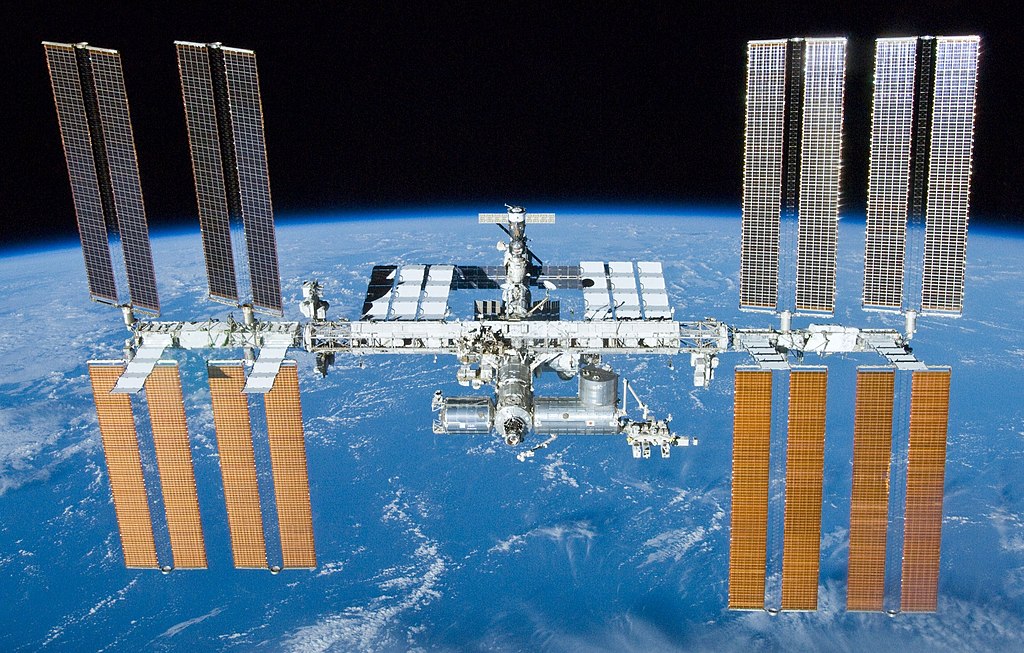

It would eventually lead to him boarding an expedition to the International Space Station (ISS) that launched on 15 December 2015.

He performed the first spacewalk outside the ISS by a British astronaut and the first man to run a marathon from space on a treadmill, before returning to Earth on 18 June 2016.

Helen Dr Sharman and Tim Peake on importance of STEM subjects

While neither carried the typical background of an astronaut, both Dr Sharman and Peake could at least call upon expertise in so-called STEM – science, technology, engineering and maths – subjects.

Dr Sharman, who also needed to learn Russian in three months at Moscow’s Star City space training site, recalls: “They were looking for people with a STEM background to apply because they needed someone with that experience in space.

“They also wanted someone who still did a practical job with their hands because they were going to do experiments in space.”

She adds: “We need huge amounts of people coming in to take up STEM subjects because they can impact on our lives in a good way.

“It’s important that young people get excited about what technology can do for them and the rest of the world.”

When speaking to young people, Major Peake is always keen to point out how STEM skills will underpin everything that is happening in space exploration.

“It’s not just in space exploration though,” he says. “Skills in disciplines like coding and AI will underpin so many future careers that we have no concept of yet and by studying these subjects in school, it will leave so many doors open.”

Helen Sharman and Tim Peake on space mission teamwork

While their careers until that point played a big role in their eventual selection for the respective space programmes, both admit the ability to work as a team was vital.

Dr Sharman says: “Teamwork is vital to any exploration, as is the planning. Without it we don’t have space missions at all.

“So they trained the astronauts how to work as a team – when to take the lead and other times when to step back and let someone else take the lead to make the best decisions.

“It’s that idea you can work interchangeably with the team.”

Three crew members boarded Dr Sharman’s mission – the other two replaced a duo who had been on the Mir space station for six months – and they all trained in a simulator of the Soyuz spacecraft in which they would eventually launch.

She says psychologists monitored how they acted together inside the craft, while other groups of people with varying specialisms also played big roles.

“I started to get a picture about how all these different people work very closely together,” she adds.

“Sometimes the boundaries merge to achieve one aim, which is a very simple goal to get a small group of people into space and back safely.

“When you put on the spacesuit, you realise you’re just a part of all the teams of people who are working collaboratively to achieve this mission.”

While up in space, Dr Sharman’s role was to perform experiments in growing food and materials but there were other requirements of her that were important to the safe completion of the mission.

“We’re trusting each other to do our jobs,” she says. “Each of us are trained to do a particular part of the docking at the space station.

“That feeling of being bonded to a group of people who trust each other completely and intensely is incredible. I’m still best friends with the people I went into space with and I hope it lasts forever.”

Major Peake believes the team effort from across the entire programme, which consists of people from different countries across Europe, is vital to a successful mission.

This is even the case when political tensions such as the Crimea conflict – in which Russian military intervened in the peninsula to take it from Ukraine’s rule in 2014 – are going on in the background.

“Certainly for the ISS partnership, there’s a common goal to make the space station as good as it can be,” says Major Peake.

“That’s not to say there’s no issues. When we were training, we had the Crimea crisis going on while working with colleagues from Russia, America, Japan – 22 countries in all – who often have political differences.

“But our common goal in the project is able to transcend those politics because it’s too important.”

Helen Sharman and Tim Peake on importance of planning in a space mission

Training for a space expedition can take at least two years and much of the planning involved sets up crew members for worst-case scenarios.

They will work with people from a range of disciplines, as well as former NASA astronauts.

“It meant if there was a problem we didn’t anticipate, we could think our way through it,” says Dr Sharman.

“Things go wrong. What if you have an emergency in space and need to make a rapid return to Earth?

“You might end up in the sea rather than on land, so we trained for how we would survive for three days in water because that’s how long it could take to be rescued.

“It meant I knew how I was supposed to be feeling at different parts of the mission. I knew that when you feel a bump, it’s an okay part of the launch.”

Major Peake’s crew was thrust into an unexpected situation early on in the mission when docking at the ISS.

One of the sensors failed and they had to abort, sending the shuttle back into space and forcing the crew to take manual control.

“It’s training, training, training that prepares you for those environments and we really do sweat the small stuff,” he says.

“The more you know your system, spacecraft, space station and spacesuit, then it gives you options.

“And that’s what generates the ability to be able to deal with difficult situations – having options.

“My fear is running out of options and that’s when it gets tough.”

Helen Sharman and Tim Peake on future technology in space travel

In 1991, Dr Sharman’s crew could communicate via radio with mission control back on Earth – but only when the spacecraft had a direct line of sight with Moscow during its orbit.

By the time Major Peake was on the ISS, he could call home 24/7 and even set up video calls with friends and family once a week from 250 miles altitude.

Over the next couple of decades, there’s no doubt the technology available to astronauts will jump forward significantly again.

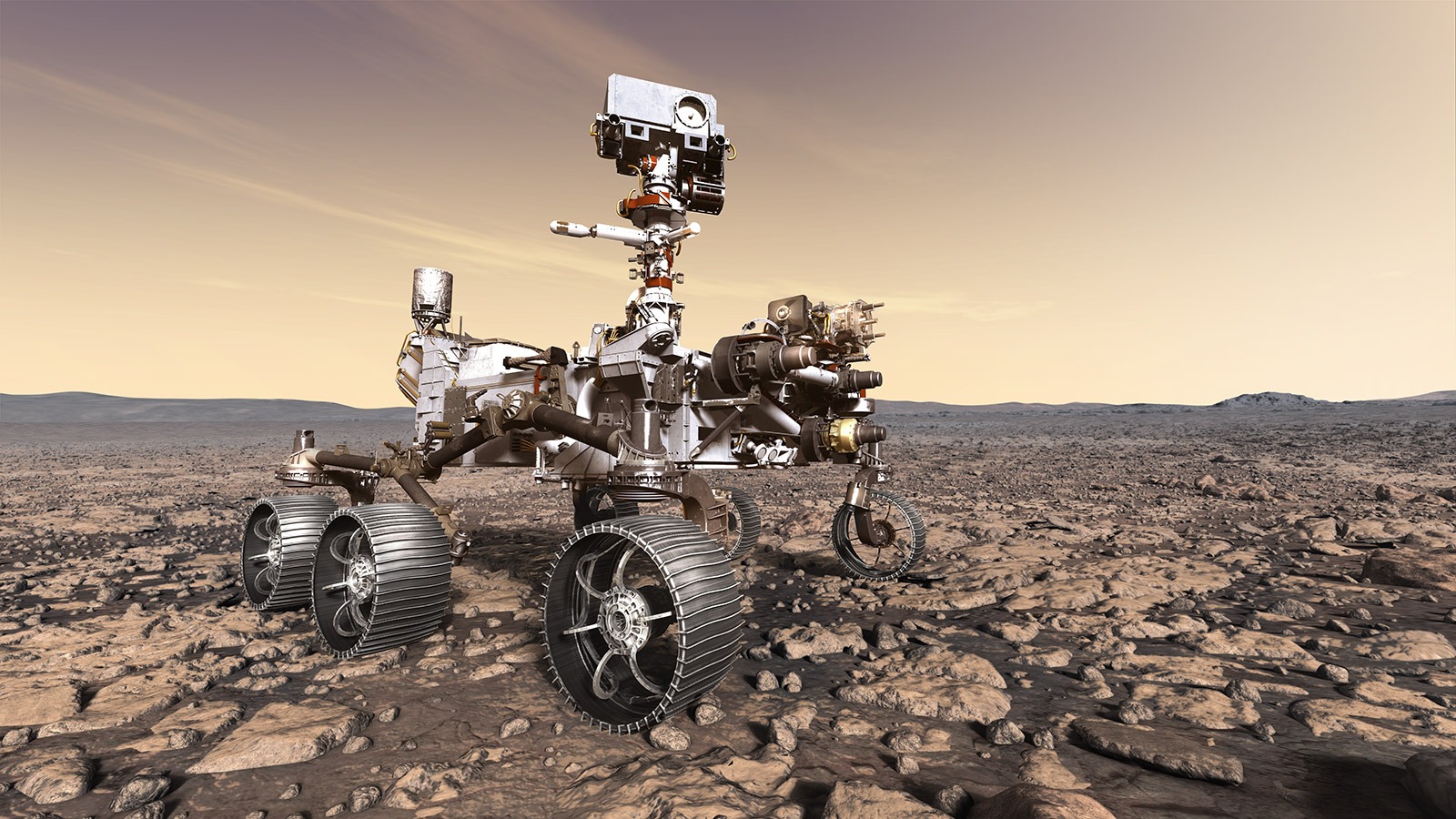

Dr Sharman believes robots will work more alongside humans to “do exciting things”, while Major Peake says humankind is on the “dawn of a new era of space exploration” because of emerging technologies such as AI.

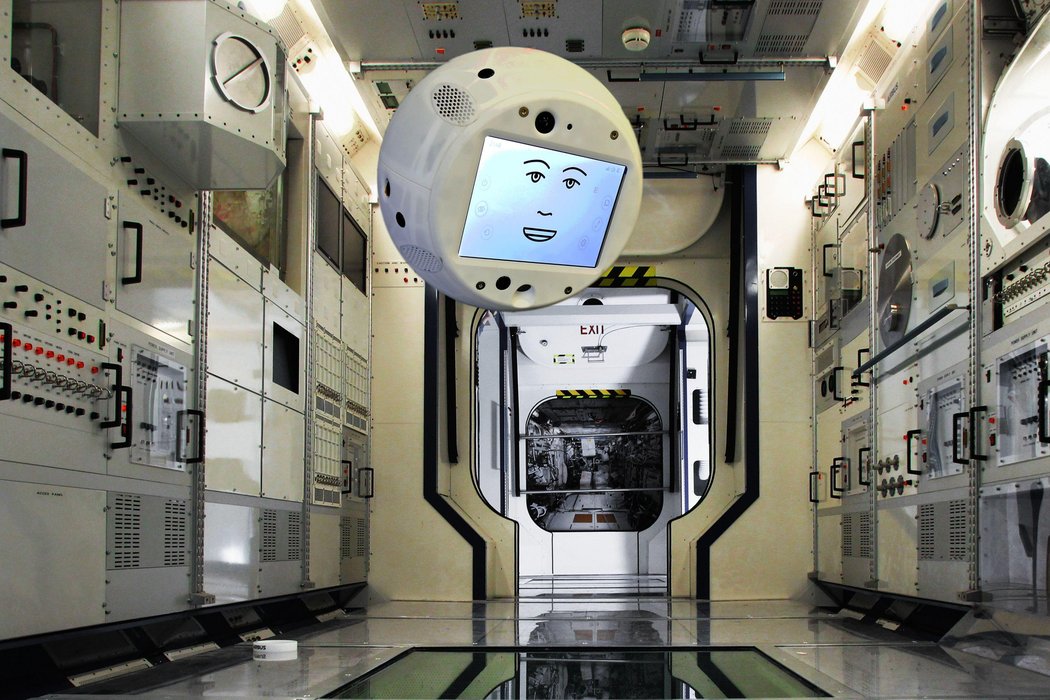

Astronauts on board the ISS can now interact with a cartoon-faced robot called Cimon (Crew Interactive Mobile Companion), which was built by Airbus and IBM.

Introduced last year, it works as an AI-based assistant that can give instructions to crew members when they carry out scientific experiments, and respond to verbal questions.

Major Peake explains: “When you look at autonomy for future missions, it’s going to start with robotics.

“There’s a 24-minute delay in communication from Earth to Mars so the Mars Rover needs to get on with tasks it’s been given.

“For the crew, it’s important to help them deliver their missions without the constant re-enforcement from mission control.”

Dr Sharman believes the future is exciting and fully expects humans to walk on Mars within the next couple of decades – using technology that hasn’t even been invented yet.

She adds: “I look back at my space mission and know that amazing things and impossible achievements can happen if we keep an open mind about new developments wherever they might be.

“If we work together collaboratively – because it’s that teamwork that’s really important – and make sure we adopt the new technology to suit our own purposes, then everyone can enjoy being part of this vast and beautiful universe.”