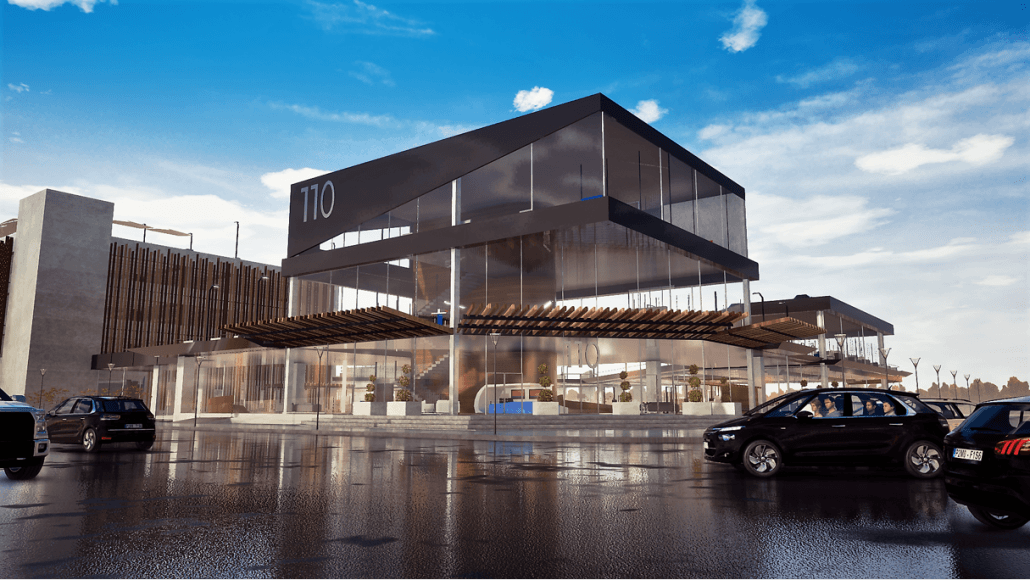

Fortnite developer Epic Games' acquisition of 3D architectural visualisation tool maker Twinmotion highlights the growing importance of immersive tech in building designs

Virtual and augmented reality is giving architects a greater insight into how their designs will look in real life

Virtual and augmented reality are not yet widely used in architecture but they are becoming a more integral part of designing buildings. Elly Earls finds out from architects how immersive technologies are creating more confidence in design decisions and why designing in a virtual world is the next logical step.

“Click on the option that says ‘One Week Ago’.”

I do as I’m told and, instantly, walls are stripped away and the corridor becomes a shell of what it was a moment ago. Next, I’m “teleported” into the centre of the building to see what it will look like when finished and occupied.

One quick click and a gold screen appears. Another and a floorboard vanishes, revealing the cabling underneath. I turn around to see desks and sofas in photo-realistic quality, and glance up and down to get a handle on the skyscraper’s epic scale.

John SanGiovanni, the co-founder of Visual Vocal, is walking me – remotely – through his company’s visualisation app, which he describes as “a PDF of virtual reality (VR); a lightweight cloud-based platform that allows very simple and efficient sharing of every conceivable type of spatial content”.

It was designed to allow distributed project stakeholders to immerse themselves into unbuilt environments, and is just one example of how VR and augmented reality (AR) technologies are being used today to improve the way architects collaborate with and communicate their designs to clients.

“If a picture is worth 1,000 words, then a VR experience is worth 10,000 pictures,” SanGiovanni says. “We’re finding that most of our customers create their first piece of VR content within just a few hours of being on our platform for the first time. Adoption has been really quite validating.”

Virtual and augmented reality in architecture is creating visual storytellers

One architecture firm that has worked closely with Visual Vocal, and experimented early on with other ways to use VR and AR, is HOK.

“We are using it mostly to communicate design stories to our clients,” says chief technology officer James Vanderzande. “Usually, you have a dozen or so key spaces you want to illustrate as part of the design story you want to communicate to your client, and VR and AR are better ways to get them immersed in that experience.”

HOK is also experimenting with what Vanderzande calls “configurators”.

“If you need to walk a client through a space and show them different options in real time – instead of showing them three or four static renderings – we can make that an interactive experience for them; they can click through a few different choices,” he explains.

This is proving particularly popular with healthcare clients, such as hospitals and laboratories. “We can walk user groups through their proposed spaces and they get to experience the layout of the equipment, cabinetry and work benches and help customise where those things will be based on a more 3D feel of the space. I’d call it a virtual mock-up,” Vanderzande says.

“If it doesn’t accelerate the process, it does create more confidence in those decisions, which reduces potential rework later in the design process. If our clients fully understand what we’re delivering earlier on, it’s less likely they will change their mind later in the design process.”

How video game industry is using virtual reality architecture

HOK started experimenting with VR and AR about three years ago in an effort to get ahead of clients who might come to them and request it. Today, less than 10 out of the thousands of projects HOK takes on every year do so.

“But it is coming,” Vanderzande says. “It’s becoming more and more frequently used. The challenge is to understand your client first and know what kind of level of technology they’re comfortable with.”

He is also seeing signs that architects are becoming an important target market for the gaming industry. Not least Epic Games’ – the developer of Fortnite, the video game phenomenon – recent purchase of Twinmotion, which offers “real-time immersive 3D architectural visualisation” and can change the weather and seasons of a site, create an animated path or transition from building information modelling (BIM) to VR in two clicks.

“This is a really important indicator that [games companies] are starting to reach into the AEC community and provide better tools,” Vanderzande says. “In five years’ time, you’re almost going to see a blurring of the lines between the BIM world and the game engine world, which I think naturally tends to include VR.”

Going one step further, there’s no question in SanGiovanni’s mind that systems like these pave the way for how architects will design buildings in the future. “That’s one of the reasons we founded this company; I’m very bullish about the potential of creating in three dimensions,” he says.

“The only reason we create within two dimensions is because the technology of sculpture has been less accessible than the technology of drawing. But imagine a world where sculpture is as easy as drawing in two dimensions, or maybe even easier and faster than 2D creation. That’s why it has such tremendous appeal.”

Vanderzande agrees. “That’s why we got into BIM in the first place – because we work in 3D components and systems, we should be designing that way. So it stands to reason that the next evolution would be going from designing in 3D on screen to 3D in VR,” he says.

However, having seen and tested a few of the tools in this space, he isn’t convinced it will catch on quite yet. “The technology isn’t as facile as it should be. Designers like tools that they’re familiar with,” he says.

“Throughout my career I’ve tried to figure out what the best design tool is and I’ve come to the conclusion that the best design tool is the one the designer is most familiar with.

“When we get a generation of designers that are comfortable working in VR; that will be when the scale starts to tip into actually designing in VR. It has to come from them. They have to own it and want to do it. In the meantime, it is an additional medium through which we can communicate our designs with our clients.”

Augmented reality architecture offers a portal into another world

AR is basically projecting VR on top of a physical reality. There are two main ways it’s currently being used by architects, according to Dogu Taskiran, the CEO of Stambol Studios, which helps architects, construction and real estate companies showcase their projects using VR, AR and other immersive applications.

“One of them is very generic,” he explains. “You can replace an architectural scale model with an AR one. The idea is that you can take the building with you wherever you go, put on an AR headset and see it on a tabletop in a boardroom as if it’s standing right there.”

But a more exciting application, he believes, is using AR to create a portal into another world.

“You can enter into an entirely new space using only your phone – so, for example, you could go and take a look at a building on an empty site, see it in its full scale with the current lighting conditions and freely roam around. That’s what AR does, without really isolating you from your surroundings.”

HOK has also had success with AR when it’s been used to show clients the potential of different sites, while SanGiovanni, who originally envisaged Visual Vocal as a predominantly VR app, has been surprised that many clients have opted to use it in an AR capacity.

“A team will pre-stage a few different architectural options at three or four or five locations as you walk through a job site,” he explains. “They then align the VV content with the real world so the client can look through the viewer and see things change before their eyes.”

What does the future hold for virtual and augmented reality in architecture?

Fast forward 10 years, he predicts, and VR and AR will no longer be two distinct things.

“You’ll buy a headset capable of both and it might be the eye glasses you’re wearing at all times or, eventually, the contact lenses you’re wearing, but you will be able to choose whether you want to turn off the real world and immerse yourself in unbuilt geometries,” he says.

“Or maybe you want to teleport someone into your space and observe them as if they’re standing there. It’s my firm belief that you won’t really be able to tell who’s actually in the space and who’s being virtually projected in.”

In the meantime, Vanderzande is excited to see more portable, wireless solutions hit the market. At present, the drawback of the most powerful headsets is that you must remain tethered to the computer. He’s also seeing people become less willing to wear headsets at all, with many clients leaning towards web or mobile-based interfaces.

I’ve just explored Visual Vocal’s app on my three-year-old Samsung Galaxy via a shaky 4G connection and been wowed. If the technology is already this accessible and intuitive, it’s easy to imagine it rapidly taking hold in the design world.

This article originally appeared in the summer 2019 edition of LEAF Review. The full issue can be viewed here.