Trade wars and Brexit have created uncertainty in international commerce - but its impact on investment decisions isn't so straightforward

Foreign direct investment is yet to return to 2007 levels despite an upturn since the global financial crisis (Credit: Unsplash/Samson)

Since the global financial crisis, foreign direct investment (FDI) has been in decline. Figures from 2018 and early 2019 show this trend is continuing, despite occasional spikes driven by one-off events. Jim Banks speaks to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) senior statistician, Maria Borga, about how the global picture is changing as we look towards 2020.

Trends in foreign trade investment do not follow a smooth curve. The figures show it to be volatile, often driven by one-off events. A global, multibillion-dollar M&A transaction can drive figures higher in a specific quarter, just as a change in tax regulation can have a short-term impact. Nevertheless, viewed over an extended period, the picture is clear – FDI is steadily falling.

Figures from the OECD show that global FDI fell by 27% in 2018 to $1.097bn. This follows on from trends in 2017, when FDI flows decreased by 16%.

“We saw a fall in FDI in 2017 and 2018,” says Maria Borga, senior statistician in the OECD’s investment division. “When the global financial crisis happened, FDI plummeted and then went flat for several years. The post-crisis peak came in 2015, but we have never returned to the level that we saw in 2007.”

Borga’s job is to look at the figures, rather than the political-economic machinations that drive them, but she has deep insight into the one-off events that drive some of the spikes and troughs in FDI flows.

“FDI is very volatile anyway,” she remarks. “Large, cross-border M&A deals can make the numbers jump from one quarter to the next, for example, and in 2018, US tax reform had an immediate effect.

“The trend in the longer term is shaped by uncertainty. There are concerns about what is happening with trade, and there is Brexit, for example, so companies are not as willing to invest.

“Some companies may not want to move around their supply chains due to changes in trade policy until these things become more certain. It is easy to forecast the effects of these changes on trade, but it is less easy to foresee the effects on investment.”

What Borga is pointing out here is that US trade wars or changes to trading relationships brought about by Brexit will evidently make trade between certain markets more difficult, but the investment choices that companies make in response to these events are not straightforward.

With Brexit, for example, a company could invest in the UK in order to sell to that market through a local subsidiary. On the other hand, it could reduce its investment in the UK, which would not provide the seamless access to the EU that it previously enjoyed, as they may prefer to shift operations to an EU member state instead.

Tax initiatives turn the tide for FDI in the OECD

US tax reform was a big driver in 2018. The Tax Cut and Reform Bill that was approved in December 2017, included a 3% reduction in the tax rate, a reduction in the single corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, revocation of alternative minimum tax (AMT) for corporations and a host of other measures. One of its aims was to incentivise a shift of corporate operations and investments to the US.

“Under the old tax code, US multinationals could defer tax on foreign earnings if they were not repatriated,” Borga explains. “After the reform, the new system became a territorial system, and it applied a tax on prior overseas earnings whether they were repatriated or not. As a result, from 2018, companies could bring money back to the US without any additional tax, so they repatriated very large amounts.

“It changed the incentive for US companies to invest in their foreign affiliates,” she adds. “The US similarly lowered tax rates, too.”

The OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) is also having an impact. The initiative is aimed at tackling base erosion and profit sharing, the goal of which is to shift profits across borders to take advantage of tax rates that are lower than in the country where the profit is made.

The OECD estimates that these tax-avoidance practices cost governments between $100bn and $240bn in lost revenue each year, which is the equivalent to between 4% and 10% of the global corporate income tax revenue.

One common practice is to use special purpose entities (SPEs), which have few or no employees, little or no physical presence in the host country, and whose assets and liabilities represent investments in or from other countries.

Their core business consists of group financing or holding activities. As the BEPS initiative enters an advanced phase, it is tackling tax havens and SPEs, largely through the implantation of information-sharing processes.

This work is already having a visible impact, and this is becoming evident in FDI flows. FDI flows to and from SPEs dropped to negative levels for the first time since 2005, due in part to large equity disinvestments to and from SPEs in Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Hungary.

Borga says: “Related to BEPS, we have seen a move away from pure SPEs, which have no physical presence or employment and exist to hold assets, partly for profit-sharing, partly for raising capital more easily in a specific country.

“This move has come about because there is now a need for income to be aligned to activity, so there are more entities that serve similar purposes to SPEs but that have a physical presence and employ people.”

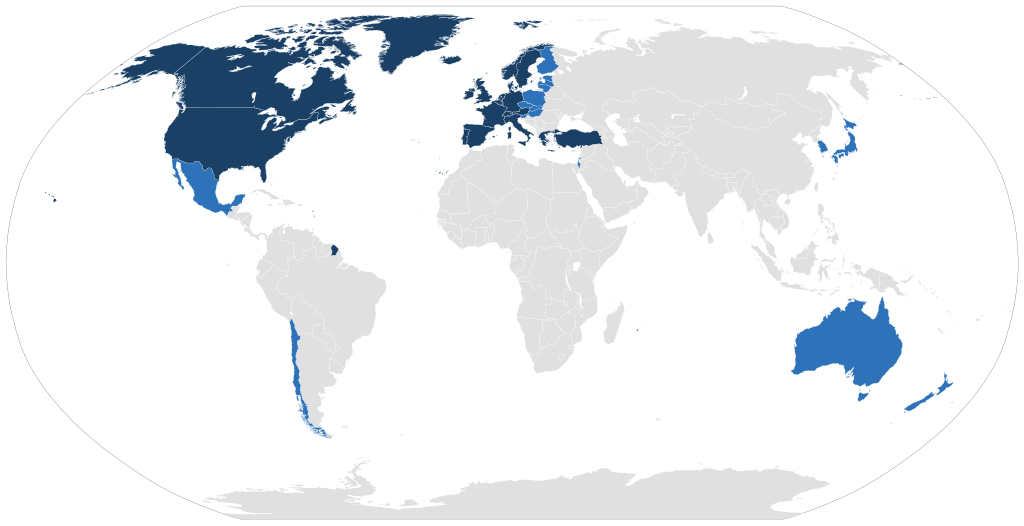

Regions realign as FDI inflows to non-OECD countries increases

During 2018, inflows to the OECD area decreased by 23%, largely driven by disinvestments from Ireland and Switzerland, and reduced flows to the UK, US and Germany. Outflows from the OECD area decreased by 41% as US multinationals repatriated large amounts of their earnings held by foreign affiliates.

Despite concerns about an economic slowdown, FDI income paid by affiliates in OECD countries to foreign parents increased by 17% and FDI income received by OECD parents increased by 9% in 2018.

“The OECD and the EU follow a similar trend because the EU countries make up a big part of the OECD,” notes Borga. “In the US, there was an aberration with outward investment due to the changes in its tax regime, and there was also some weakness in terms of inward investment, though that trend has reversed.”

In 2018, FDI inflows to non-OECD G20 economies increased by 8% while FDI outflows decreased by 26%.

“Driven by US tax reform, inward investment into the EU was slow in 2018, having fallen quite a bit,” she adds. “The picture for the G20 is different because non-OECD members – China, Indonesia, India and others – saw inward investment increase.

“In addition, their outward investment increased following the financial crisis. This was largely driven by China, which in 2016 became a net-outward direct investor for the first time.”

The changing cast of investors in OECD FDI

The changes in regional flows show that the traditional leaders of outward FDI are steadily changing. Japan, China and France were the largest sources of FDI outflows worldwide in 2018, but investment from China, which has been such a powerful driver of the market for many years, has been in decline for the past two years.

“China had become a big buyer of assets around the world, but it has pulled back in the past couple of years,” says Borga. “China was sustaining FDI as the US, UK, France, Switzerland and other traditional major sources of investment decreased their outward FDI in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis.”

China may be impacted by the simmering trade wars with the US, and there are concerns over declining exports, outflow of capital and a weak currency. China’s role in global investment is to be watched in 2020; it is too early to view clearly.

“In the second quarter of 2019, FDI fell by 42% from the first quarter, but it might just have been volatility or a slow quarter, so it is hard to predict the long-term trend,” explains Borga. “So far this year, however, the non-OECD G20 is the only region we track seeing an increase in terms of inward investment.”

“We are seeing FDI income falling from pure financial centres such as the Cayman Islands, and increasing from places such as Ireland and the Netherlands, where companies have a real presence and benefit from some fiscal advantages,” Borga explains.

“That could be an impact from BEPS, but it is hard to link FDI and BEPS as we cannot tell from FDI statistics what taxes companies are paying. The use of SPEs can be an indicator, but it is not a perfect indicator.”

Looking ahead, the longer-term effects of the tax reform are hard to predict. While outward FDI flows from the US in the second half of 2018 recovered from negative values in the first half, US outward investment is likely to be lower going forward due to reduced reinvestment of earnings in foreign affiliates.

Though global FDI may well continue to decline through 2019 and 2020, the behaviour of the key players – not least China and the US – cannot be foretold. So, it is therefore wise to be prepared for any eventuality.