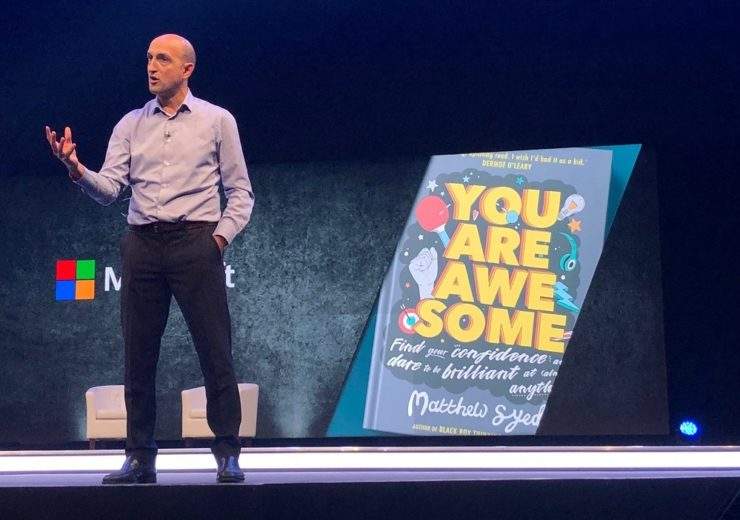

Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking theory was explained in detail as the broadcaster and author took to the stage at Microsoft Future Decoded 2018

Matthew Syed speaking at Microsoft Future Decoded 2018

He’s hit the mainstream as a broadcaster, journalist and author, but Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking theory stems from his time as an international table tennis player.

When he became England’s number one ping-pong star for the first time in the mid-1980s, he realised the majority of the top players all came from the same street – Silverdale Road in Reading.

They enjoyed no particular privileges – Syed says it was “an ordinary suburb of an ordinary town in South East England” – while there was no genetic mutation, extraordinary funding or nepotism.

Instead, the frequent BBC collaborator, who has won awards for his books and journalism for The Times, says: “We had a great coach who was a fantastic leader and got us into the right mindset, with the right learning experiences.

“With wonderful leadership, great passion and healthy competition, a very ordinary cohort of people became extraordinary table tennis players.”

It inspired Sayed to deconstruct psychologically what enables people to reach the “summit of our potential” – and leading him on to Black Box Thinking.

What is Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking theory? The fixed mindset versus the growth mindset

The name – also used for his 2015 book on the subject – stems from the black boxes retrieved from crashed airplanes so investigators can learn what happened and learn lessons for the future.

This is an example of a “growth mindset”, which Syed pits against the “fixed mindset” when he splits people into two categories.

The fixed mindset describes how people believe their basic qualities, such as natural talent or a high IQ, are fixed traits that will lead to success on their own – without any need for development.

“Many people think that to have a successful organisation, you need to hire people of that ilk,” says Syed, giving a keynote speech at the Microsoft Future Decoded 2018 conference in London yesterday (1 November).

“And perhaps many of us will agree this isn’t completely false, and it’s a phenomenon that explains some of the variations we see in performance.”

But on the other side of the spectrum is the growth mindset, occupied by people who believe their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work.

Syed explains: “In the growth mindset, people say talent isn’t irrelevant but in a complex world, it isn’t enough.

“They focus too on other ingredients that lead to success, like constant self-evaluation and recognition that ‘however good I am, even if I’m a genius or a leader at one of the most prestigious institutions in the world, I can nevertheless get better’.

“This might mean learning from mistakes, failures and suboptimality.

“I’d suggest this dichotomy between fixed and growth mindset explains a great deal about differentiators in performance in the world we live in.”

Syed explores his theory of the contrast between these mindsets in the differing behavioural instincts of two huge industries, aviation and healthcare.

Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking theory in aviation

Given the black box analogy, it’s no surprise Syed points to aviation as a trendsetter for the growth mindset.

He says: “There’s a recognition deep in the culture of the industry that even though they are smart and talented – and employ sensible protocols, procedures and behaviours – there’s a fundamental sense of the suboptimal in which they understand they’re not as good as they might be.

“Not because they lack intelligence but because the complexity of the phenomena. When you’re trying to keep a non-linear dynamic system straight, you can see why that warrants a mindset in which the professionals in the industry are always looking for learning opportunities.”

Syed said the number of “near-miss events” – the industry name for when pilots narrowly avoid collisions in mid-air or on the runway – occur very regularly but are openly and transparently recorded.

It means data is available so those involved can learn how to adapt processes and avoid similar mistakes from happening again.

“Second by second, minute by minute, hour by hour, the industry is learning the lessons to drive the dynamic process of change,” says Syed.

“What if, God forbid, a crash happens, the most serious form of system failure? If you’re anything like me it’s sometimes quite difficult to confront and interrogate our failures, particularly if you’re supposed to be smart, senior and competent.

“Aviation insists on having a mechanism that makes these failures data-rich – the mechanism being the black box.

“So the investigators of an accident can rescue the box from the rubble of an accident, investigate what went wrong and systems can be put in place to make sure the same mistake never happens again.”

He says the results of having such an adaptable organisation is that, while eight of the US Army’s 14 pilots – more than half – died in 1912, only one in every 17 million take-offs, while no major airlines crashed at all last year.

Syed adds: “Is it partly to do with the talent in the industry? Yes. But I’d suggest it’s also to do with this culture of continuous improvement and learning.”

Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking theory in healthcare

In healthcare, the most senior people are more talented than those in aviation, Syed believes – saying they often come from more expensive education and possess higher IQs.

But he says this is an industry that is prone to harbouring the fixed mindset as it deflects the opportunity to learn from the most serious issues.

“There’s something quite deep in the clinical culture, where you get to the top of the hierarchy where as a consultant, you don’t make mistakes,” he says.

“This sounds great but what if there’s a suboptimal – that’s to say something goes less well than it could have done?

“Is it fair to say that’s basically anything? You can get better at any performance-related dimension through time.”

The most serious form of suboptimality in healthcare, of course, is death.

But when a doctor talks the family of a deceased patient, Syed believes there’s a tendency towards self-justification and concealment.

Elaborating on self-justification, he says: “If I’m super-talented and typically get everything right, and then someone has died, my mindset is it can’t be anything to do with me – it must be an unavoidable death.

“The fixed mindset takes the sting out the mistake but obfuscates learning.”

Until recently, Syed says 45,000 people died every year in the US alone because of central line-associated bloodstream infections – which often occur during operations.

Senior doctors believed for decades these were unavoidable until a doctor carried out an investigation and found clinicians were missing a key step.

“Of course it’s not because they’re lazy or bad people, but because they’re busy and didn’t realise they had to make this step,” says Syed.

According to the Journal of Patient Safety, about 200,000 people die every year in the US due to preventable medical errors – making it the third biggest killer in the country.

Syed adds: “The problem in healthcare isn’t a lack of talent. The problem is when talented people are in the wrong mindset, their energy doesn’t go towards innovation and rational change.

“All too often, sometimes on a subconscious level, it goes to self-justification.”

Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking theory in Microsoft

In a conversation with Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella last year, Syed asked him how he had led the software giant on a renaissance, helping it to triple its share price by this summer after years of a stagnant stock price under predecessor Steve Ballmer.

Under his influence, the company has moved away from proprietary phone hardware and operating systems to centre its business around subscription products that secure a regular revenue stream.

“Often, executives think of culture as something that’s a big soft and fluffy – something HR people talk about to justify their existence,” says Syed.

“But Satya thinks his task as CEO is to curate the culture. One of the issues at Microsoft was it got to a fixed mindset so he had to get it into a growth mindset.

“He said Microsoft had a huge amount of historic success but that brought a bit of complacency.

“People became know-it-alls, everyone wanted to look like the smartest person in the room.

“So if you want to hear that, you don’t want to hear about the errors and what competitors are doing better.”

Syed says that kind of mindset in management suppresses the mindset of others to keep on improving, adding there’s a need to move from an organisation of “know-it-alls to learn-it-alls”.

A “learn-it-all wants to hear about their errors and what the opportunities for growth are.

“At Microsoft, it wasn’t the talent or psychological environment that changed – it was the social dynamic,” says Syed.

He adds: “The growth mindset doesn’t mean talent doesn’t matter – it’s about liberating our talent.

“It’s to interpret what someone is saying about something I could better not as an indictment of who I am if I’m supposed to be an expert but as an opportunity.

“Because in a complex world, there’s a huge amount that even experts don’t know.

“Expertise isn’t just about current knowledge, it’s about finding out what we don’t know as quickly as possible. This is a psychological problem as much as anything else.”