Big Blue's vice president of Exascale Systems, David Turek, discusses how high performance computing can curate workplace and industry knowledge to help companies develop their institutional memories

High performance computing can help businesses of all varieties collect and exploit the vast amounts of specialist knowledge being created each year relevant to their organisation. IBM’s vice president of exascale systems David Turek speaks to Andrew Fawthrop about the tools “Big Blue” is developing to enable companies to preserve and develop their own “institutional memories”

As the implementation of technology across all levels of modern society and industry continues to increase, so does the amount of data and information being produced – and this is now happening at a rate far beyond the capability of humans to digest and understand it all.

For businesses, this raises the issue of how best to capture the knowledge and expertise that is built up within an institution and its employees, and to retain this for future prosperity.

Using its expertise in high performance computing (HPC), IBM has developed an approach to collecting and preserving such knowledge – often termed “institutional memory” – to ensure it is not lost by an organisation.

The US information technology giant has developed the world’s two most powerful supercomputers – Summit and Sierra – and is using its proficiency in this field to tackle the gap between the rate at which information is being produced and the human capacity to consume it.

Speaking to NS Business at the ISC High Performance conference in Frankfurt last week, IBM’s vice president of exascale systems David Turek explains how his firm is developing automated tools that create searchable “living knowledge graphs” based on vast amounts of evolving data.

He says: “It’s a programmatic effort on our part, to help people capture as much as they can about what they know, and be in a position to deploy it to gain commercial strategic advantage.”

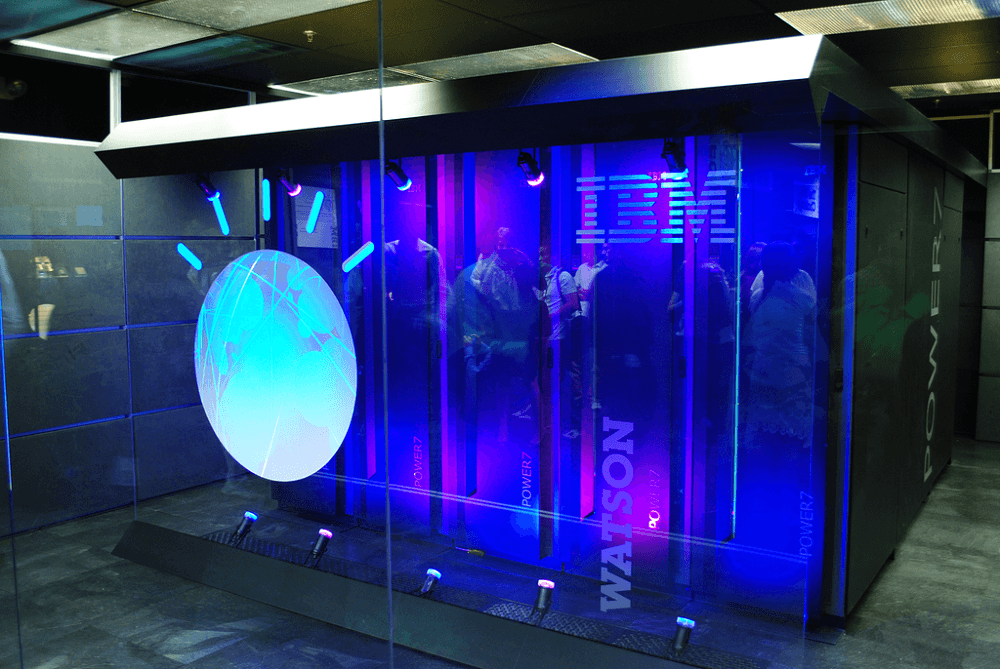

IBM is using high performance computing to preserve institutional memories

Mr Turek, who has spent almost 20 years working on technical computing at IBM, explains that as the world becomes increasingly “awash” with data, much of the most interesting information to companies remains “unstructured” – stored away in filing cabinets, notebooks and people’s heads.

And when workers with expertise leave their job for whatever reason, the knowledge they have acquired during their time in the role risks being lost by the organisation they depart.

Mr Turek says: “The loss of an employee is a real blow to most companies, especially the smaller to medium-sized businesses.

“When you lose somebody who’s worked in a field for 20 years and they have expertise that you can’t begin to imagine, it has a huge impact – if you think you’re going to hire somebody fresh out of university, and train them for a couple of months to give you the same thing, it’s just not realistic.

“So we’re hopeful that companies will begin to use this technology in multiple ways, one of which is to build up an institutional memory by using these tools to help extract things out of your head and on your desktop, or filing cabinet or phone, and organise that.

“But then in concert with other data sources, to also create the possibility of information exploration that was never there before.”

For Mr Turek, this is a technology that can work in any industry, with IBM currently supplying the service to between 25 and 30 commercial entities worldwide, ranging from chemical and material companies to pharmacy and biological firms.

IBM has been working on the project for about four years, with many of these knowledge aggregation services available as part of its Watson HPC programme.

IBM has developed ‘accelerated discovery’ tools to create searchable living knowledge graphs

Not only is the amount of data being collected within individual businesses proliferating at a high rate, but so too is the collective knowledge base of broader society, across all sections of academia, industry and culture.

Mr Turek envisions companies being able to cross-reference their own individual institutional memories against a wider knowledge bank, as a way to create new perspectives for problems unique to each particular organisation.

He says: “The amount of knowledge that is being generated on an annual basis is growing at a fantastic rate – and its growth rate has outstripped the scalability of humans to digest it.

“In a world where knowledge no longer scales at human level, what do you?

“We have built a set of tools that are part of what we call ‘accelerated discovery’.

“It begins by automatically ingesting voluminous amounts of data, and then automatically turning that data into a connected graph of representational connectedness among all the data.”

These repositories of information can be searched using natural language processing, with the algorithms able to understand complicated questions and give answers in an organised way, based on all the connected data relevant to the search.

Mr Turek says: “This is beyond databases. This is beyond just zeros and ones.

“This is about the implementation of an information architecture that allows you to look at data as knowledge and explore it very systematic way.

“As a user, all you need to do is specify the questions and everything else is there, and the automated tools are helping to build these things.

“Essentially, what we have is a system that is learning from the information being passed to it, continually reinterpreting the relationship between different data elements, and creating a sort of living knowledge graph as more information gets put into it.

“We’ve been developing algorithms and architectural approaches to search and understand these graphical representations really, really, fast – maybe 1,000-times faster than anyone else.”

Commercialisation of tools to preserve institutional memories benefits businesses outside major tech regions

A key purpose of these tools for IBM is to “democratise” automation technology so that businesses not based in major tech hubs like San Francisco, New York or London are not disadvantaged by their location.

Mr Turek explains that the concentration of technology expertise is big cities around the world currently means that “to really get effective use” of tools like artificial intelligence and data analytics, firms need to be located in these places to tap into the skilled workforce that resides there.

He says: “Right now, getting value is really dependent on your ability to hire skilled data scientists.

“What we’ve done for tools is put a real focus on automation every step of the way.

“Because there’s nothing illegitimate about a business being in the middle of Germany, as opposed to being in Munich, Frankfurt, or Berlin – just as there’s no difference between a company being in the middle of the United States or in New York, San Francisco or LA.

“So the purpose of automation is to begin to democratise the tools, so that the company which has a problem can get to the point of using them without having to go and try to hire rare, exotic and expensive data scientists.

“We can use data that’s now been put in this form, and we have tools that will automatically generate neural net models to answer questions that are as good as, or better than, anything a human can do.

“So now, if you know nothing about the science of AI, natural language processing or deep learning and machine learning, you’ve got tools that can help you get there and start making progress on these fronts.

“That’s an important element of what we’re trying to do here.”