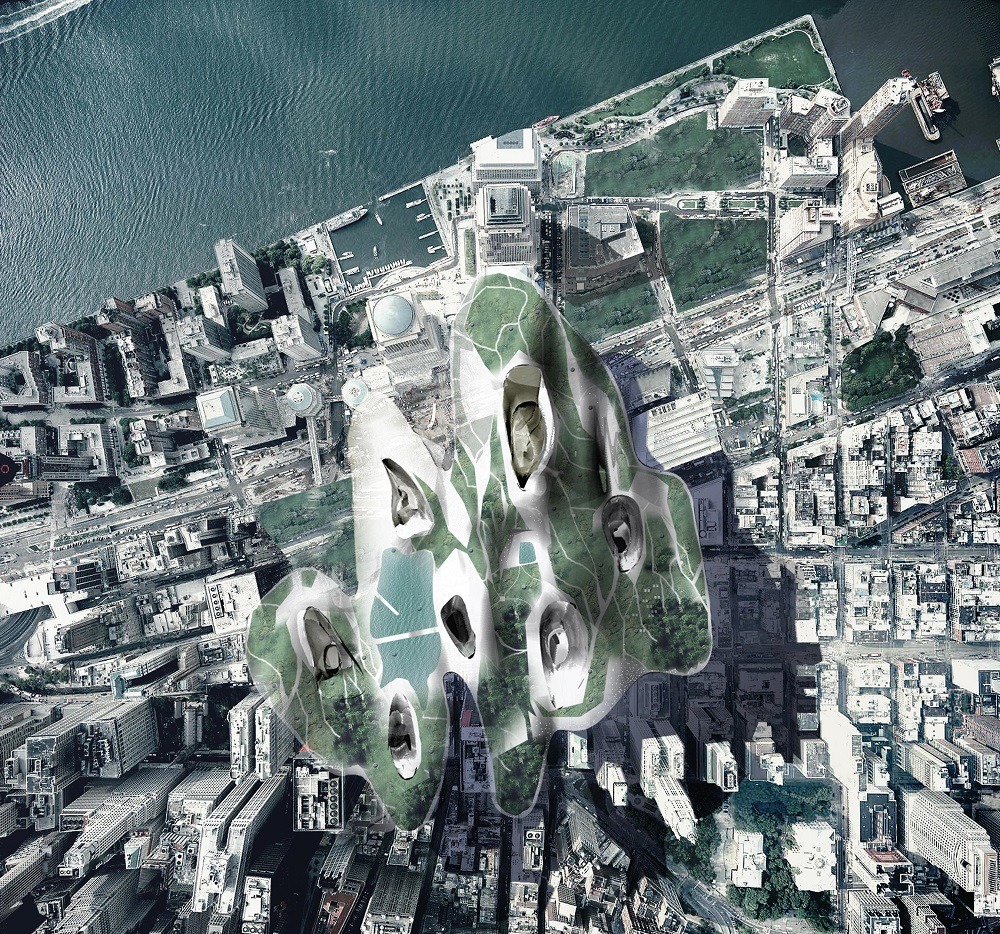

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles has borrowed a Chinese architecture style, while a proposal for the rebuilt World Trade Center would have reimagined the traditional US metropolis

Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles (Credit: MAD Architects)

With Chinese architects taking on prestige projects across the world, and the precipitous growth of its cities redefining our understanding of the urban experience, what might we expect from this emerging school of architecture? Tim Gunn talks to Ma Yansong of MAD Architects, Du Juan of Hong Kong University and Urbanus’s Meng Yan about the influence of this style in western cities.

There was a million-tonne wound gaping across lower Manhattan, and Ma Yansong was dreaming.

In the waking world, it was 2002, Ma’s last year as one of Zaha Hadid’s graduate students at Yale. By crane, truck and bucket, workers were excavating the void at the base of the fallen World Trade Center.

The question of what could repair the scars left when two of the world’s tallest structures had sliced downwards into their foundations was the defining architectural issue of the new century. If they were going to graduate, Hadid wanted to see her students rise to it.

“I couldn’t do it,” Ma says simply. “Everyone was doing so much research, because that was a really complicated project – whether you should build a memorial, or replace it all, or build something else. I did all the research I could, but I just didn’t have any conclusion. Then I had a dream.”

How World Trade Center plan followed a Chinese architecture style

He dreamed of a cloud, a park and a city. Or, more dynamically, he dreamed of a cloud that lifted the city upward, sprouting a park as it did so – the two crossing and recrossing along their improbable trajectory. The next morning he sketched out an irregularly curved landscape building suspended over the old block.

It was with that “Floating City” proposal, a reimagining of the quintessential American metropolis – vapours in place of filing cabinets, organism instead of machine – that he first rose into popular consciousness.

“Maybe I’m just not good at logical thinking,” he says, “but if all our work is based on research into reality, the results will only reflect the same reality.”

For Ma, his is a distinctively Chinese approach to architecture. The World Trade Center plan was an early iteration of his “shanshui city” design philosophy. Literally, that term translates as “mountain water”, but the genre of classical Chinese landscape painting that it designates doesn’t take much literally. Nor is it simply metaphorical.

Instead, the 1,600-year-old tradition of inking streams and outcrops according to a very specific set of conventions is an expression of the belief that, to quote Ma, “nature is the spiritual extension of human beings” – or something like a dream.

As Ma sees it, working in Europe and North America – home to so many of the individual buildings that he studied and learned from – demands he think in those terms.

“When I started, I had to ask myself why I was there and what I could offer that was new,” he explains. “It has to be what I can bring from China. I believe that’s a different understanding about nature.”

Mystery is key to Chinese city Suzhou’s architecture style

A year after Ma proposed letting that emotional understanding play out above the New York skyline, Du Juan, who had emigrated to the US with her family after the Tiananmen massacre of 1989, left nearby Princeton to spend a semester of her own graduate course in the Chinese city of Suzhou.

By studying its UNESCO-protected classical gardens, she hoped to gain a perspective on the relationship between architecture and landscape that she couldn’t get from a western education.

The proverb is, “Paradise in Heaven, Suzhou and Hangzhou on Earth”. On the immaculately sunny day she first entered one of the city’s ancient gardens, Du, who is now the associate dean of architecture at the University of Hong Kong, was moved to tears by its beauty and design intelligence. Even then, almost all the locals she spoke to insisted she should really see it in the rain or snow.

“Intuitively, you’d think sunny days are better times to visit,” Du says. “But it wasn’t about that in Suzhou. It was about mystery – it was about the architecture and landscape evoking something other than what is specifically and determinedly there.”

That attitude to weather is partly conditioned by lifetimes’ worth of poetry and discussion about Suzhou’s architecture, but it’s worth bearing in mind that almost none of that took place in response to completed gardens.

Each space was developed over centuries by a succession of owners and planners whose goals didn’t include completion. The gardens morphed and grew in response to the reactions they prompted.

“Take how important we’re taught programme is,” continues Du, jumping back to the western model of architectural education. “In the gardens, most of the buildings aren’t programmed. They’re named according to their relationship to the landscape and the view you would look upon while occupying a certain moment.

“The way to understand the gardens wasn’t the objects – not the buildings, the rocks or the water – but the relationship between these elements, including the person.”

George Lucas’ museum borrows from Chinese architecture style

Ma also describes Beijing, the city he grew up in, as something like an “imaginary landscape” of the type that more often appears in literature. Fittingly, then, it was George Lucas, creator of some of the most popular imaginary landscapes of all time, who finally chose to build one of Ma’s “clouds”.

While it won’t block out the sun over Los Angeles, the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art is going to have a park on top, and it is going to stand out.

That’s a blessing and a curse. MAD originally won the competition to build the Lucas museum in Chicago, beating out an illustrious field that included Hadid, but the development stalled after local residents objected to the design of that building and its position on public land on the banks of Lake Michigan.

So Lucas lost his site, but he kept his man. The museum relocated to the west coast, and MAD came up with a design that Ma, who describes certain shots in Star Wars as “poems about time”, feels replicates the appropriate “strangeness” and “mystery”.

He could be describing the Suzhou gardens when he says, “You want it to be friendly, but you also want to keep the distance between people and the space. Then people will feel attracted; they’ll want to discover.”

Du was attracted by a different mystery. From the home of some of classical China’s greatest cultural achievements, she went to a city just out of its teenage years – the area that most exemplifies the country’s modern contradictions: Shenzhen.

Village life for China’s own Silicon Valley in Shenzen

The mega-city dubbed the “Silicon Valley of Hardware” is an unusual place. The statistics make that much clear.

Whereas the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs defines a city as a contiguous space with a population of 300,000 or more, there are at least that many people in a single Shenzhen Foxconn factory. Oh, and roughly half of the city’s 12 million to 20 million inhabitants live in villages.

“In a way, there are two parallel Shenzhens, or two parallel realities in the city,” explains Meng Yan, co-founder of Urbanus, a practice and think-tank based jointly there and in Beijing.

“There’s the generic Shenzhen everybody knows – the 40-year-old miracle city that worships top-down planning and design – and there’s also this unplanned, informal city intertwined with it. The real miracle is their coexistence.”

Indeed, rather than improvised slums or shanty towns, these so-called urban villages are actually the ancient settlements that existed before paramount leader Deng Xiaoping declared the area China’s first “special economic zone” in 1980.

While their farmland was transferred to the new city authorities, the villagers retained control of their residential plots. Development of these areas was officially illegal, but millions of Shenzhen’s residents now live there, their lives shaped by the decisions and family dynamics of farmers and truck drivers who grew up in traditional clan villages.

As such, the enclaves often help immigrants from rural areas adapt to the demands of life in the city. Like “wetlands”, Meng explains, each absorbs new elements and adjusts to the surrounding conditions. Together, they foster diversity right across Shenzhen. They’re even home to a new generation of young architects.

Here, Du found an intricate process of urban compromise that seemed to respond hour-by-hour to the kind of relationship concerns that had shaped Suzhou’s gardens through dynasties.

Using a Chinese architecture style to ‘build the dreamscape’

It was 2005, the year of the first Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture and of the plan to destroy the 2,000 “poisonous tumours” leeching off the city’s unprecedented growth. Both were initiated by the Central Planning Bureau. Both also focused on the urban villages.

As part of the Biennale’s curatorial team, it was Du who convinced the city planners to support an exhibition about the areas the regional party secretary had designated a cancer. The event began a difficult, unsteady re-evaluation of Shenzhen’s urban informality, and the biennales have become an important mechanism for facilitating communication between locals, architects and government planners.

In 2017, Meng and Urbanus curated the seventh almost entirely in Nantou village; and last year the city promised to maintain at least 70% of Shenzhen’s remaining enclaves through the next quarter century.

For Du and Meng, the exhaustive research and political pressure that have helped make that shift possible are motivated by more than nostalgia. As its economic growth slows, the latter believes “the city as a whole may find a kind of salvation by looking at these alternative ways of developing”.

In contrast to the surrounding grid, Meng thinks of the self-sponsored mutations of Shenzhen’s dense urban villages as a higher definition development model than central planning can achieve.

“It’s a non-stop urbanisation process,” he says. “And each building is like a mini-Manhattan block. You can open a shop anywhere, and the next day you can make it an apartment, an office, or a community space. It’s a constantly changing condition compared with the city we build.”

Observing this process has humbled both architects. “It’s a challenge because we’re trained to design, we’re trained to predict, dictate and build,” explains Du, who just finished a book on the city’s history. “But Shenzhen shows that we need to know what not to build, what not to control, and how little we can predict.”

“It’s important to build the dreamscape,” Ma says cryptically. If we look close enough, we might find it’s doing that by itself.