Changing payment trends are pushing the UK increasingly towards a cashless society, but not everybody is ready for a digital switchover

The UK is turning its back on cash (Credit: Warner Bros)

A cashless society is an increasingly realistic prospect in the UK as more and more people turn to contactless and digital payment options. But there are plenty of warnings about a complete switch away from notes and coins, with many groups still dependent on cash. Andrew Fawthrop looks at some of the the major payment trends driving this movement, and considers some of the important issues in the cashless debate

The days of crumpled bank notes and misplaced coins rattling around pockets are quickly fading, as hard cash is phased out of many people’s daily lives – replaced in most cases by contactless bank cards and smartphones.

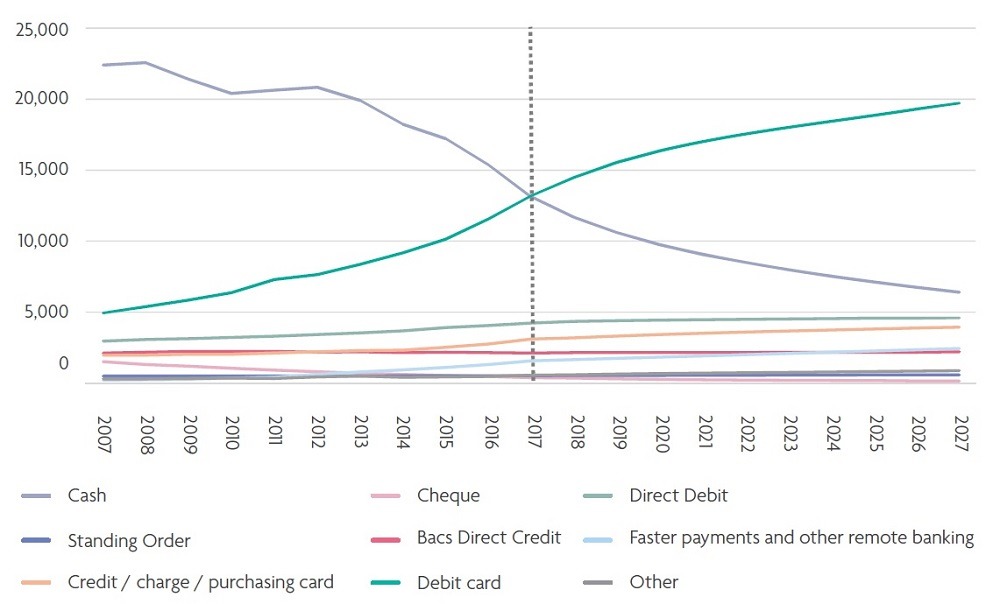

Research by trade association UK Finance shows the proportion of cash payments in the UK fell from 61% to 34% between 2007 and 2017 – and the downward trend is projected to continue, with just 16% of payments expected to be made in cash by 2027.

A shift towards a fully cashless society has been widely debated – but while such a prospect might be welcomed with open arms in tech-savvy parts of the country, by fashionable types flashing hot coral plastic and clever watches, large sections of the public are unready for a complete currency switchover.

Andrea Nitsche, co-initiator of the pro-cash campaign group Cash Matters, says: “Going cashless is not a choice consumers make, it’s a choice made for them by market players reducing access to cash – for commercial reasons.

“Freedom of choice is important. Not only for reasons of social inclusion – even though that’s very important – but also for the groups that need cash in their daily lives. Many people choose cash, and for a variety of reasons.

“Cash is legal tender, accessible to everybody with no access restrictions. It is the most democratic means of payment and a great societal equaliser.

“It is also the only means of payment that protects privacy and personal data, and is the only form of public money, with no hidden costs or fees.”

UK Finance figures show that while there were 3.4 million UK consumers who almost never used cash at all in 2017, there were still 2.2 million who predominantly did choose cash when shopping.

UK payment trends show cashless spending is on the rise

Cash use in the UK is waning, largely as a result of the emergence of new technology, online banking and retail trends.

Today, about one-third of payments are made using cash – half the amount of a decade ago, and in another 10 years this is expected to fall to around one in every 10 transactions.

Contactless bank cards – which were introduced in 2007 in the UK – are the main factor behind the steady demise of cash, giving customers a simple and convenient way to pay.

The upcoming trial of new biometric debit cards by NatWest could signal a future where even high-value point-of-sale transactions can be made with an easy tap.

Similarly, mobile payments – contactless transactions made via a smartphone using platforms like Google Pay and Apple Pay – are also becoming increasingly popular, with 561 million mobile payments made in the UK in 2017.

This figure is forecast to grow by 56% to 877 million by 2027.

For small retailers, like market traders and cafés, which would have previously relied on hard cash as the main currency to keep their businesses running, there are now low-cost portable card readers like iZettle, Square and SumUp, which can process contactless card and smartphone payments.

Even the Church of England is getting in on the act, with a digital collection plate being trialled in some parts of the country that allows worshipers to donate with a contactless payment.

The growth of open banking in the UK has seen rising interest in innovative ways of interacting with money through online apps and platforms, further shifting the focus of money management away from cash and towards digital.

Fewer ATMs and bank branches reduce the availability of cash

The demise of UK bank branches has been well-documented in recent years – with most, but not all, of the UK’s lenders looking to reduce the size of their brick-and-mortar networks.

Figures from consumer group Which? found that more than 2,500 cashpoints were shut in the second half of 2018, and more than 3,000 bank branches have closed their doors in the UK since 2015.

There are currently around 65,000 cash machines in the UK, 40% of which are owned and operated by bank branches, and so each time a new set of shutters go up, the amount of free-to-use cashpoints goes down – a significant fact, given that 90% of cash is accessed via ATMs.

In response to this trend, Which? teamed up with the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) to launch a campaign called “Freedom to Pay. Our Way”.

It aims to raise awareness of how access to cash is becoming more difficult, and the impact this could have on consumers and small businesses.

FSB national chairman Mike Cherry says: “The rapid pace of bank branch and cashpoint closures is hurting small businesses all over the UK.

“Millions of small firms have customers who want to pay using notes and coins. The vast majority of shoppers either use cash frequently or want to see access to it maintained.

“Bank branches and cashpoints create a natural draw for high streets and town centres.

“They give shoppers a reason to visit, meaning increased footfall and greater sales at surrounding small businesses as a result.

“Going cashless should represent a genuine choice for small business owners.

“It shouldn’t be a move forced by lack of access to deposit and withdrawal facilities, disappearing ATMs or high cash-handling fees.

“With our cash infrastructure increasingly under attack, it’s time for a regulator to be given explicit responsibility for protecting access to notes and coins.

“Otherwise, we risk drifting into a cashless environment that we’re simply not ready for yet.”

The Access to Cash Review warns against a fully cashless society

“Sleepwalking into a cashless society will leave millions behind. Action is needed now.”

This was the frank warning delivered to the UK finance industry and government policymakers in March 2019 by an investigation into the UK’s drive towards becoming a cashless society.

The Access to Cash Review looked at how the rise of digital payments is impacting demand for cash in the UK, and what the move towards a cashless society means in real terms for consumers and small businesses – as well as the infrastructure used to keep cash flowing around the country.

It concluded that 17% of the UK population – more than eight million adults – would struggle to cope in a cashless society.

The group, which has since warned that the UK’s cash infrastructure is close to actually collapsing, wants parliament to hand extra powers to regulators and introduce rules forcing banks to provide suitable access to cash for customers.

“There are worrying signs that our cash system is falling apart,” warns the review’s chairwoman Natalie Ceeney, whose career in senior leadership includes heading up the Financial Ombudsman Service.

“ATM and bank branch closures are just the tip of the iceberg – underneath there is a huge infrastructure, which is becoming increasingly unviable as cash use declines.

“If we sleepwalk into a cashless society, millions will be left behind. We need to guarantee people’s right to access cash and ensure that they can still spend it.

“There is huge scope for innovation, not just in digital payments but also in cash.

“We need leadership of this critical issue from our regulators and government, but success will rely on banks continuing to properly support their customers who rely on cash.”

Options for improving cash access could include making cashback a more attractive option to shops by changing the rules on card fees, launching home delivery schemes for cash, or promoting the role of the Post Office as being a source of currency – and not just when going on holiday.

The report positions the issue of cash availability in the UK as a matter of urgency for government, banks and regulators, calling on them to preserve the cash infrastructure that many people continue to rely upon.

Responding to the findings, Treasury select committee chairwoman Nicky Morgan adds: “The complexity of this issue cannot be overstated, but the simple truth is that leaving the future of cash to be determined by market forces will not work.

“Tinkering around the edges to preserve the status quo will not work. It’s clear that something more fundamental is needed.”

Who will continue to depend on cash?

The elderly are often cited as the demographic most likely to struggle in the event of a cashless switchover, but many different sections of society are vulnerable.

While age is an important consideration – with 25 to 34-year-olds most likely to use contactless payments, and those over 65 least likely – economic factors are estimated to have a bigger influence in terms of readiness for going cashless.

Speaking in March 2019 at a retail banking conference in London, the Financial Conduct Authority’s chairman Charles Randell addressed the subject of cash access.

“Whether you’re old or young, if you’re poor, online banking means access to a computer or paying for data on your phone,” he told attendees.

“Issues people in this room probably don’t have to think about.

“Mobile banking, cashless transactions and a range of other technological developments may mean a wonderful life for some people, but we mustn’t forget that, for some time to come, others will need access to cash or bank branches.”

Many people on low incomes depend on cash for budgeting reasons – with the advice from debt charities often being to get rid of cards, and focus on cash as a way to budget more effectively.

If you can hold the money you have to spend in your hand, it is easier to keep track of how you are managing it day-to-day.

There are budgeting tools now being built into mobile banking apps, but this is wholly dependent on regular access to both the hardware and online infrastructure that these apps require – something that cannot be presumed.

Bhavika Shah, payments analyst at UK business intelligence firm GlobalData, says: “Many marginalised and vulnerable groups rely on cash as their main payment method, and the UK moving towards a cashless society could lead to consumers losing control over their finances.

“As a consequence, this could raise consumer debt levels in the UK, as budgeting is often more challenging when paying with digital payment tools.

“Similarly, the UK becoming an entirely cashless society would completely exclude those who do not have a card or other electronic payment tool – which is likely to be recently-arrived immigrants and the homeless, as they may lack the necessary paperwork to open an account.”

Regional differences can play a part too, with rural communities particularly exposed, when access to broadband or 4G mobile coverage is patchy at best.

Many businesses in these places also don’t accept card payments for similar reasons, making cash an integral part of these rural micro-economies.

In the context of all these factors, cash dependency versus digital payments becomes part of a much bigger discussion about society and how it is governed.

As Mr Randell told his London audience: “The declining use of cash plays into a much broader debate about financial inclusion which includes the future of communities in a digital age, the way a range of public services are delivered, and consumer education.

“We need to discuss not just who should pay for the cash system, but also what action government and local authorities should take to support people to adapt to a world where cash may not be accepted.”

Declining usage puts cost pressures on the cash infrastructure

On the other side of the equation, commercial outfits running the UK cash infrastructure – such as LINK, the major ATM network operator – are finding that as less use is made of physical currency, the more it costs to keep it accessible.

The Access to Cash Review estimates the total cost of maintaining this country-wide infrastructure to be about £5bn ($6.5bn) per year, with most of the costs – which are covered mostly by retail banks and commercial operators – being fixed.

This is an important point because it means the charge to operators remains largely the same, regardless of how much their services are being used.

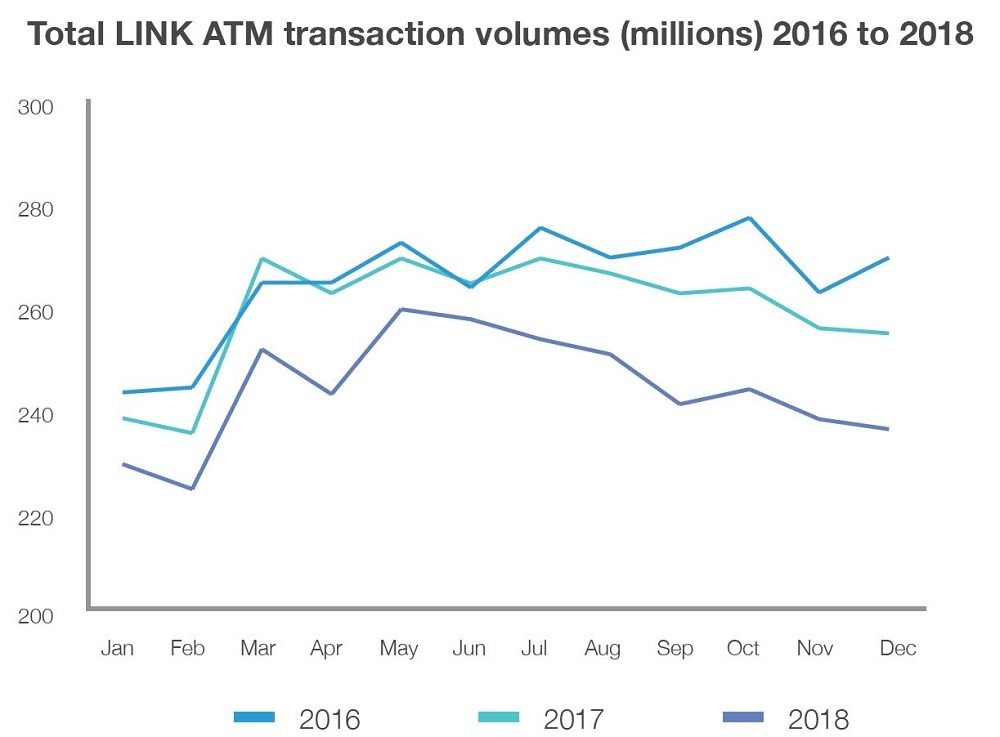

Data from LINK shows the number of cash withdrawals from its machines fell by 5% in 2018 compared to the previous year, while the value of the cash withdrawn fell by 3.5% over the same period.

So as the demand for cash continues to decline, the costs of running the services that ensure its availability get higher – leaving commercial operators with big decisions to make about how they structure their operations.

The Access to Cash Review noted that the end result of this situation will likely mean costs being passed on to the consumer in some way or another.

“As cash use declines, the economics of the current cash model are becoming seriously challenged,” it notes.

“Much of this dynamic is not seen by consumers, as we are used to getting our cash for free.

“But ultimately, consumers do bear the costs – even if they are currently subsumed into the UK’s retail banking model.

“But just as rising costs have given us smaller chocolate bars instead of higher prices, we’re seeing the pressure of these higher unit costs manifesting in the withdrawal of services.”

This article was originally published on 3 April 2019